Management Practices to Reduce Mycotoxins in the Field

The last several corn silage production seasons have been challenging for farmers in the upper Midwest U.S.A. These challenges have also been seen in other parts of the world and on other crops. One of the biggest problems has been the occurrence of high mycotoxin levels in finished feed. Wheat and wheat straw have also been plagued with these issues.

One of the most significant mycotoxins during the past few seasons has been deoxynivalenol (i.e. vomitoxin). Vomitoxin is produced by several species of fungi in the Fusarium group. One of the most important species contributing to this problem is Fusarium graminearum (also known as Gibberella zea).

Vomitoxin, like other mycotoxins produced by fungi, are the result of secondary metabolism. This means that the fungus doesn’t necessarily need these compounds to thrive and survive, but might be produced in times of stress experienced by the fungus. Regardless of what drives mycotoxin production in the fungus, cropping practices and weather conditions over the past several seasons have favored the development of vomitoxin in silage corn and wheat.

Resistance in hybrid silage corn and wheat is considered only partial. This means that there are varying levels of resistance, but no hybrid or variety is completely immune. We also see the widespread use of brown midrib (BMR) corn hybrids when it comes to silage. These hybrids are generally more susceptible to pathogens, and it seems that they might be to Fusarium spp. as well. We have also seen a trend toward pushing relative maturity (RM) in hybrid corn, in addition to increasing planting population. This can cause added stress to corn plants that can render them more susceptible to infection. These cultural issues combined with warm and abnormally wet weather during the flowering stages (the growth stages that are most likely to be infected by Fusarium spp.)in corn and wheat, are the likely reasons we have seen increases in vomitoxin over the last several seasons.

Scroll for more

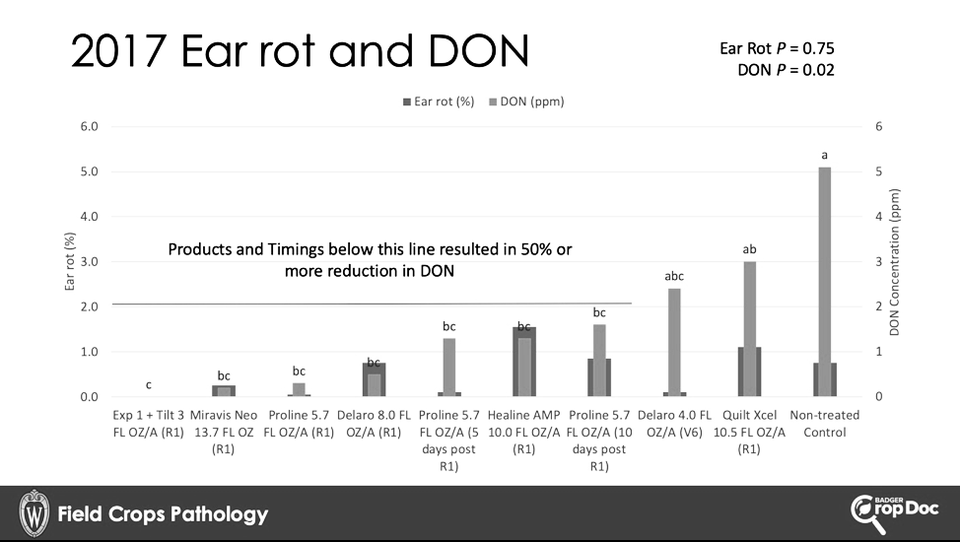

Treating silage corn, grain corn, and wheat with fungicide has become a common practice in many areas of the world including the Midwest U.S.A. There are many fungicides on the market for boosting plant health, controlling foliar diseases, or for reducing mycotoxin levels. But which products work and what application timings provide optimum control? The Field Crops Pathology Laboratory at the University of Wisconsin-Madison has been investigating this over the last several seasons in both wheat and silage corn.

Applications of fungicide sprayed at the start of flowering up until about a week after the start of flowering are optimum application-timings to maximize efficacy of fungicide for reducing vomitoxin in both wheat and silage corn. This makes sense as the practice of applying fungicide during this time, protects flowers from infection by Fusarium spp. in both crops.

The best use of fungicide

Scroll for more

Scroll for more

See Fig.1

Applying fungicide prior to flowering or two weeks or more after the start of flowering, will not result in optimum reduction in mycotoxin levels. Products that contain fungicides in the triazole group, tend to be the best products for reducing mycotoxins. In wheat, the best fungicides for reducing mycotoxin levels (if applied at the right timing) have been Prosaro, Caramba, and Miravis Ace. In silage corn, Proline has the been the go-to product, however several other mixed-mode-of-action products such as Headline AMP and Miravis Neo have resulted in decent reductions in vomitoxin in silage corn (Fig. 1). Products containing only a strobilurin, should be avoided in wheat and corn, if sprayed during flowering, as these products can actually increase the level of vomitoxin.

Note that the application of fungicide only results in about 50% reductions in vomitoxin compared to not-treating. This means that this practice should be combined with other cultural practices and variety or hybrid choices to reduce vomitoxin to acceptable levels. Managing plant stress through reducing seeding rates and choosing appropriate RM can help plants deal with infection from fungi like Fusarium and maximize the use of protectant fungicides.

Treating silage corn, grain corn, and wheat with fungicide has become a common practice in many areas of the world including the Midwest U.S.A. There are many fungicides on the market for boosting plant health, controlling foliar diseases, or for reducing mycotoxin levels. But which products work and what application timings provide optimum control? The Field Crops Pathology Laboratory at the University of Wisconsin-Madison has been investigating this over the last several seasons in both wheat and silage corn.

Applications of fungicide sprayed at the start of flowering up until about a week after the start of flowering are optimum application-timings to maximize efficacy of fungicide for reducing vomitoxin in both wheat and silage corn. This makes sense as the practice of applying fungicide during this time, protects flowers from infection by Fusarium spp. in both crops. Applying fungicide prior to flowering or two weeks or more after the start of flowering, will not result in optimum reduction in mycotoxin levels.

Products that contain fungicides in the triazole group, tend to be the best products for reducing mycotoxins. In wheat, the best fungicides for reducing mycotoxin levels (if applied at the right timing) have been Prosaro, Caramba, and Miravis Ace. In silage corn, Proline has the been the go-to product, however several other mixed-mode-of-action products such as Headline AMP and Miravis Neo have resulted in decent reductions in vomitoxin in silage corn (Fig. 1). Products containing only a strobilurin, should be avoided in wheat and corn, if sprayed during flowering, as these products can actually increase the level of vomitoxin.

Note that the application of fungicide only results in about 50% reductions in vomitoxin compared to not-treating. This means that this practice should be combined with other cultural practices and variety or hybrid choices to reduce vomitoxin to acceptable levels. Managing plant stress through reducing seeding rates and choosing appropriate RM can help plants deal with infection from fungi like Fusarium and maximize the use of protectant fungicides.

Reproduced with kind permission of by Dr. Damon Smith from University of Wisconsin Madison

Scroll for more